I arrived Belo at about 3:05 p.m. The sun was bright. People of every age filled Three Corners, moving in all directions as trade pulled them along. It was Friday, Belo market day, and the place was alive. Music of every kind blasted from shops and stalls. Car horns cut through the noise. Commercial bikes slipped through gaps that didn’t exist a second before. People nudged forward in crowded lanes, chasing small errands and bigger hopes.

Students from Government High School Belo, Acha Baptist College, Baptist Comprehensive High School, and others hurried past in their uniforms. Watching them, I felt a tug in my chest. Wasn’t that nostalgia? On market days, when I was at GHS Belo, it was hard to keep my eyes on the board, not because I had plans or money to shop, but because I couldn’t wait for school to close so I would run to Three Corners which always felt too full of life on such days. Three Corners on Belo Market days always felt like a floating bubble.

That was May 2016.

In March 2017, a close friend lost his mother in Sho – a village about 20 minutes’ drive from Belo. We left Bamenda to attend the funeral. When we reached Belo, the streets were almost empty. Armed men patrolled in silence. A hard knot formed in my stomach. Travellers were pulled over. Passengers stepped out one by one, checked with guns pointed their way.

I was with my friend and another young man. Our voices shook as we walked towards the checkpoint. This was the same Three Corners I knew from seven years of school. The same square that held my teenage memories and my dreams of coming back home one day. But the bubble had burst. Since then, nothing has felt the same.

To get to Sho, we had at least two checkpoints ahead: first the military, then “Amba” fighters. Given how many people had already lost their lives, we were afraid. We left the road and took the bush path. For more than two hours, in bad weather, we dropped into valleys, climbed long hills, and crossed narrow, shaky bridges. The good news is we ended up making it to Sho; and were able to make it back to Bamenda that same day. It felt like we’d cheated death.

As I write, Belo is quiet and scarred. Many families fled as fighting grew; and those that stayed back lived in gunshots and buried loved ones, friends or strangers on a daily basis. Given that men were hugely targeted, it got to a point where women were forced to bury corpses because all the men/boys had fled from the security forces.

School became history as all schools in Belo shut down. A few lucky students found places in other towns and tried to continue, often in hard conditions. Many did not. Some went as far as joining the separatist fighters, commonly referred to as “Amba” fighters. So many lives have been lost – women, men, and children alike. IDP (Internally-displaced Persons) is now one of the most used abbreviations in Francophone cities where most Anglophones have sought refuge.

I asked around recently and gathered that a few private schools have reopened in Belo and nearby. Government schools have not because the separatist fighters think that the government has no jurisdiction in these areas and their schools should not operate. On May 20, 2024 during the commemoration of Cameroon National Day, the mayor of Belo at the time, Dr Ngong Innocent, his deputy and an inspector of basic education were shot dead in Belo. That is how heavy the air still is. For years now, the Belo Rural Council has been operating mostly from Bamenda.

Belo sits in Boyo Division, one of seven divisions in Cameroon’s North-West Region while the South-West Region has six divisions. This makes up the English-speaking part of Cameroon and they have all been affected by the crisis, albeit to different degrees. The crisis began in late 2016 with protests by lawyers and, soon after, teachers. What started as a clear set of complaints grew into something harder and darker as government forces opened fire on unarmed protesters. Secessionists saw this as an opportunity to recruit youths to fight for the for what they considered the liberation of Ambazonia.

Today, people in Belo, like everywhere else in the English-speaking part of Cameroon, are caught in the middle – between government forces and separatist fighters. Every quiet day is counted is as a blessing, while the next dangles on the thin, almost-breaking string of dwindling hope. Home doesn’t feel like home anymore. All most people ever prayed for now is a normal day, life without gunshots and schools with open doors for their children. Nine years have gone by and not much has changed.

Before we start a war, we should ask: can we stop it?

It takes an idiot to start a war; but it takes good men, determination and time to stop one. What began as a peaceful protest in 2016 grew into a conflict that now shapes daily life – markets, schools, roads, even the silence at night. Every gain on one side seems to open a new wound on the other. The cost keeps growing.

Lives lost

No one has the exact count. According to Human Rights Watch, “at least 6,000 civilians have been killed by both government forces and separatist fighters. Civilians across the Anglophone regions continue to face abuses by multiple actors involved in the crisis, including sexual and gender-based violence.” Though this number might not include every case, it tells us how wide and deep the pain is.

Students who have left school

According to a UNICEF report published May 2, 2025, “While 2,460 primary and secondary schools remain closed in the North-West (NW) and South-West (SW) due to insecurity, leaving 223,000 children without access to education, UNICEF and its partners provided access to formal or non-formal education to 16,358 children in the two regions.” While applauding the great job done by UNICEF thus far, there are still 206,642 students without access to education. This wouldn’t have been the case had there not been war going on in these regions.

A June 2025 UNICEF publication titled Situation of Children in Cameroon further corroborates how bad the situation is by stating that “41% of schools are not operational, leaving 2249 children out of school and increasing the risk of recruitment into non-state armed groups.”

Houses that have been burned

There has been serious destruction of properties to deprive people of their housing and this, according to sheltercluster.org, has affected over 10,000 families in Cameroon since the beginning of the crisis.

The Humanitarian Situation in Cameroon

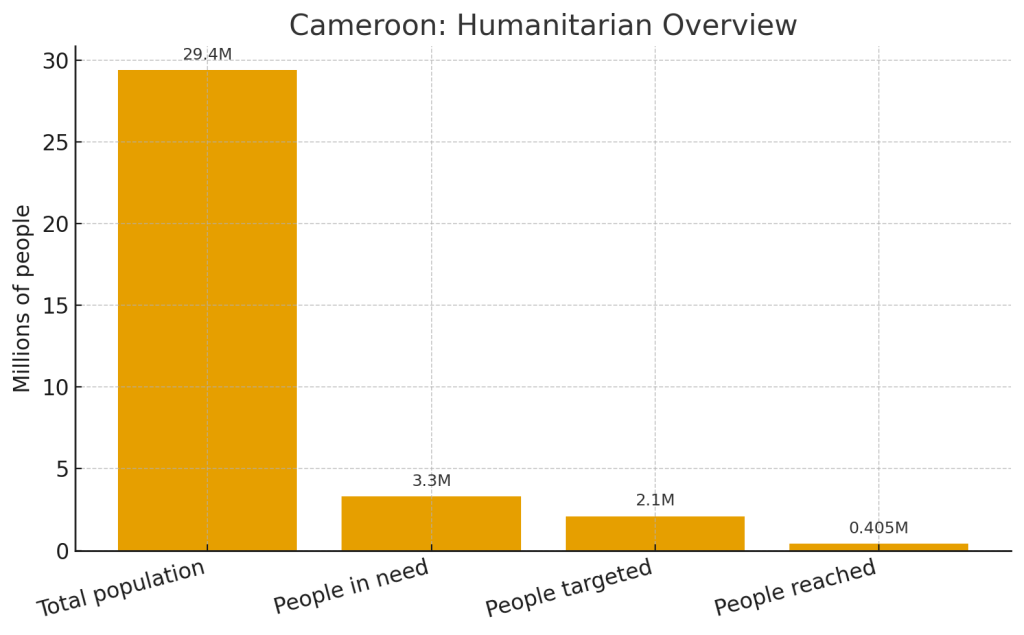

The humanitarian situation in Cameroon is currently not a good one. According to UNICEF, “Cameroon continues to face the compounded effects of three concurrent and protracted humanitarian crises: the Lake Chad Basin conflict, the North-West (NW) and South-West (SW) crises, and the impact of the presence of Central African refugees in the eastern regions.” Statistics on humanitarianaction.info as of October 8, 2025 says out of Cameroon’s 29.4 million population, there are 3.3 million people in need, with 2.1 million people targeted and only 404.8 thousand reached so far. The chart below gives a clearer view of the situation:

New ills plaguing Cameroon as a result of the crisis

In Anglophone regions, there’s been growing kidnappings, illegal “taxes” from separatists, extortion from government forces, lockdowns typically known as “Ghost Towns and attacks on education, among others.

Issue 66 of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect’s R2PMonitor states that “separatists have banned government education and frequently attack, threaten and abduct students and teachers, as well as burn, destroy and loot schools. These attacks, as well as strict lockdowns imposed by armed separatists, have robbed children of their education.”

It also adds that “During May armed separatists allegedly abducted approximately 50 women in the north-west region for protesting against violence and separatist-imposed illegal taxes. Some of the women were reportedly tortured with guns and machetes.”

I find the description of the situation on acleddata.com even more telling: “Anglophone armed separatist groups in Cameroon are deeply engaged in illicit activities to finance their rebellion, along with the rising use of violence against civilians. In the first six months of 2024, the Northwest region is the second most dangerous administrative region for civilians in Africa, only surpassed by al-Jazirah state in central Sudan. The groups’ engagement with illicit economies includes the extensive use of abductions for ransom — one of the many practices that put civilians at risk.”

How people have been trapped

As I mentioned earlier, every new day is a blessing in these two regions as the fear of the unknown constantly looms like a nightmare over the people. People now live between checkpoints and threats. Travelling and transportation have become very difficult and exorbitant as one road is blocked by one group while the other side is blocked by the fear of the opposing camp. When movement itself becomes dangerous, ordinary life starts to suffocate. On the government of Canada travel website – travel.gc.ca – the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon have been blacklisted for travel: “Avoid all travel to the North-West and South-West regions due to clashes between armed groups and security forces, civil unrest, armed attacks, the risk of kidnappings and banditry.

In summary, life in these regions revolves around curfews, lockdowns, ghost towns and normal days as decided and imposed by separatist fighters. You may ask why the people have to respect these guys. The answer is simple: for the love and fear of their lives. These are usually supervised by government forces who constantly move around in armoured military trucks, covered from head to toe and carrying scary guns.

What is the way forward?

The situation in Cameroon is complex and I can’t pretend to have the solution all figured out. However, from a more humanitarian perspective than political, I have the following suggestions.

- Protect Civilians. This may be war, but even war has its own basic rules. There should be no shooting at homes, schools, markets and hospitals. Also, there shouldn’t be kidnappings and forced taxes or extortion.

- Let help in. During such difficult times, a lot of people are affected and ensuring or agreeing on safe access so aid can reach them on every side becomes very necessary as people need food, health, water and learning spaces.

- Make schools zones of peace. Attacks on schools should completely stop and students shouldn’t be forced to boycott school. Also, teachers shouldn’t be kidnapped for teaching children who are the future of tomorrow. Where possible, catch-up classes and flexible options for children who lost years should be organized.

- Cool the ground. We should seek to push local ceasefires that can be checked and renewed as saving lives today is how trust starts tomorrow.

- Talk – about real things first. Genuine discussions should be held around safety, detainees and safe roads for markets and the reopening and safety of schools. Once this is done, harder politics with patience and truth can be handled.

- Repair what hold community together. The basic things that form the foundation of every community are water points, hospitals or clinics and classrooms. Families need help to rebuild homes that were burnt. To enable people to stand on their own again, small works and/or business should be supported. But this can only go well too in a society where people can freely walk around and engage in activities.

- Measure progress in simple ways. How many days are quiet? How many women, men and children have a rebuilt roof over their head? How many classes open? Such information that seem small at first sight should be constantly published for people to see change and work towards it.

The best way to end a war is to never start one at all; and the best way to never start one is to treat others the same way we would like to be treated.

Tubuo

Leave a comment